130, Suyeonggangbyeon-daero,

Haeundae-gu, Busan, Republic of Korea,

48058

NEWS & REPORTS

Subtly but boldly, Hong Sangsoo is treading into a new realm

- Source by KoBiz

- View4862

How the cinematic artistry of one of the most prolific auteurs of our time evolved in the 2020s

Right Now, Wrong Then

※ The contributions of external writers may differ from the opinions of KoBiz & KOFIC, and they do not represent the official views of KOFIC.

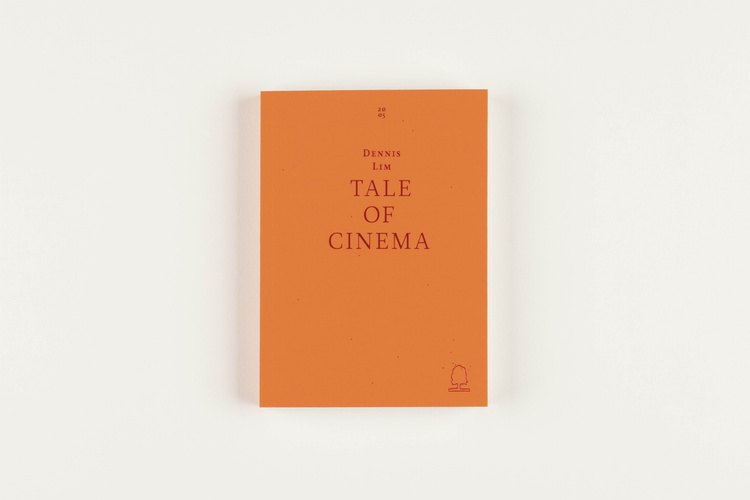

Hong Sangsoo occupies a curious place in the world cinema landscape. He is at once an omnipresent and an elusive figure, both fixture and outlier. Those of us who watch, program, and write about his work know how difficult it can be to keep up. There is always a new Hong film. He leaves no time for anticipation and little room for reflection. I know this problem acutely having recently written a book on Hong, Tale of Cinema (2022). The book is part of the Decadent Editions series from Fireflies Press, which consists of 10 monographs, each focusing on an emblematic film from the century's first decade. I chose to write about Hong's sixth feature, but wanted as well to engage with his entire body of work, knowing full well that I was chasing a moving target. When I first started researching the book at the very end of 2019, Hong had 23 features to his name; as I finished it two years later, he was about to premiere his 27th. Now, another two years on, the tally stands at 31 features in 28 years.

This is an almost unheard-of pace in contemporary cinema, and at 63, Hong shows no sign of slowing down. Quite the opposite: He released seven features in the 2000s, and twice as many in the 2010s. Since 2020, he has already produced eight (with a ninth completed and likely to premiere soon). Hong is the rare filmmaker who was not slowed by the pandemic. Within his streamlined cottage industry, he has lately taken on more roles, including serving as his own cinematographer; he works these days with a crew of four. To put it simply, Hong has achieved abundance through a radical reduction of means. He funds each movie with the proceeds of his previous films, and he makes his films as he goes. After selecting actors and locations, he enters production without a script; every morning, he writes the scenes on the docket for that day or the next. Since he uses much of what he shoots, he can edit an entire feature in as little as a day or two. This modest and pragmatic approach produces works of paradoxical complexity, notable for their breezy irreverence and their emotional and philosophical depth.

The Woman Who Ran

Five of Hong's eight films from this decade have premiered at the Berlinale, four of them in the Competition, and one of them (In Water, 2023) in a parallel competitive section called Encounters. There is a clear affinity for Hong's work on the part of the now-departed Berlinale programming team, headed from 2020 to 2024 by artistic director Carlo Chatrian and head of programming Mark Peranson, who were also in charge of the programming at Locarno when Hong won the Golden Leopard (still his biggest festival prize) for Right Now, Wrong Then in 2015. It is notable that all of Hong's films that premiered in the Berlinale competition have won major awards: Best Director for The Woman Who Ran (2020), Best Screenplay for Introduction (2021), and the Grand Jury Prize (the runner-up award) for both The Novelist's Film (2022) and A Traveler's Needs (2024). His other recent films also had high-profile festival premieres: In Front of Your Face (Cannes, 2021), Walk Up (Toronto, 2022), and In Our Day (2023, Cannes Directors' Fortnight). At the New York Film Festival, where I am the Artistic Director, we have so far screened all of them in our Main Slate.

The standard line on Hong is that his many movies are all, in some sense, the same movie. But this is only partly true, and to charge him with repeating himself misses the point. Repetition for Hong is both subject and structuring device, and, like any artist who works with this strategy, he finds meaning in the subtlest variations, coaxing compelling moral dramas from prosaic scenarios. Hong's 2020s output is notable for introducing new dynamics into his work. I'm struck, for instance, by the recurring emphasis on intergenerational relationships (often between child and parent, or child and parental figure), largely absent in earlier films. The autumnal tenor of his work has deepened. The current phase is distinguished by a deep melancholy and, in some cases, a grounded spirituality: the prayer-like In Front of Your Face counts as his most direct and emotional reckoning with mortality. His playful approach to structure and form continues to unearth surprises: The Woman Who Ran, Introduction, and A Traveler's Needs are multi-part stories but all quite different in their deployment of repetition, ellipsis, and internal rhyme. In Our Day puts a fresh spin on the bifurcated form that he has employed since his earliest films. Instead of his more common experiments with time, Walk Up uses space - here, the floors of a Seoul apartment building - as an organizing principle. And in one of his boldest gambits, In Water is shot, largely and to varying degrees, out of focus, resulting in some of the most improbably beautiful and painterly images in his filmography.

A Traveler's Needs

From the start, Hong's films have been seen as loosely disguised self-portraiture - he could be said to encourage this reading by populating many of his movies with filmmaker characters who resemble him in more ways this one. In this regard, given Hong's recent problems with his eyesight, which he has discussed in interviews, In Water is an especially moving acknowledgment of vulnerability. The Novelist's Film reflects certain aspects of Hong's relationship with actress Kim Min-hee, and is also about as close as he has come to dramatizing his filmmaking process. The title character - a blocked writer played by Lee Hye-young, an especially welcome recent addition to the Hong company of actors - is compelled on the spur of the moment to make a movie, her first. Assuring those who wonder if her idea is too vaporous, the novelist insists: "It can be simple!" She concedes that it is "similar to a documentary," though there will also be a story. But crucially, she adds, in effect describing Hong's own philosophy: "The story won't prevent the real things emerging from the situation I set up."

For the first half of his career, Hong's films went largely unreleased in the U.S. But of late, he has found a loyal regular distributor in Cinema Guild, and surveys of his work have been fairly frequent. I organized a then-complete retrospective at Film at Lincoln Center in 2022, presenting the films as multiply configured double features (we called the program "The Hong Sangsoo Multiverse"), and there have also been tributes at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, California; the Harvard Film Archive in Cambridge, Massachusetts; and the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles. Having programmed Hong's films in New York for more than a decade, I have seen his audience grow exponentially, to the point that he has attained something resembling cult status, not least among younger cinephiles and filmmakers. I suspect this is partly because his way of working is about as close as the industrial medium of narrative cinema can get these days to true independence. As an industry category, "independent film" has long lost all meaning, hollowed-out even as a marketing term. The independence that Hong has sought is more literal, more complete: a liberation, to the largest extent possible, from the strictures of time and money. If he is one of the most significant filmmakers currently working, it is not just because he does so much with relatively little but also because he stands for freedom at a time when it is in such short supply.

About the writer

Dennis Lim is an internationally acclaimed writer, film critic, and film curator based in New York City. Since 2013 he has been the Director of Programming at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, currently serving as the Artistic Director of the New York Film Festival. He served as a jury for multiple film festivals including Sundance, Cannes Critics Week, and Locarno. He has written for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Artforum, and Film Comment, and taught film studies at Harvard University and art criticism at NYU. His publications provide unrivaled expertise and insight into great filmmakers of our time: his 2015 book The Man From Another Place delves into the artistry of director David Lynch, and his latest book, Tale of Cinema (2022), is a monograph on the Korean auteur Hong Sangsoo. (https://firefliespress.com/taleofcinema)